Introduction

I recently wrote an article about the importance of the Bible as a foundational text that is necessary for fully understanding the Great Books of the Western World. There is no doubt that this is very important, which was reinforced recently when I read Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment for the second time. We simply must understand how human beings in these works of literature view the world. Faith grounded in the Bible is a major element in many of the Great Books.

Prior to the rapid spread of Christianity, the western world had a far different set of beliefs. The Old Testament narrative was the dominant worldview of the Jewish people, but they represented a very small minority. The Greek Gods of antiquity held far more influence in the lands around the Mediterranean and beyond. Anyone who has read The Iliad and The Odyssey understands how central the Greek Gods were to those stories and how bewildering it can be to keep track of the many different Gods and their various powers, not to mention their family relationships and quarrels.

I am not completely unfamiliar with the Greek Gods, but other than in Homer’s epics, I have rarely encountered them in my reading. As I started my Great Books plan, I did not feel like my cursory knowledge of the Gods was too much of an impediment as I began reading Plato. However, the third reading in my plan included two of the plays of Sophocles and I must admit that the references to the Gods became bewildering during my first reading. It occurred to me that reading Sophocles, along with his contemporaries, without a more complete understanding of the Greek Gods would be similar to reading Dostoevsky with only very limited exposure to the Bible.

It became obvious that I lacked important foundational knowledge that would hold me back in terms of understanding Sophocles and would certainly prevent me from actually enjoying the plays. It also occurred to me that I probably have only a cursory understanding of Homer as well. I decided to step back from my reading plan in order to seek out the equivalent of a “Greek Bible” that I could use as a reference.

The Greek Bible?

Earlier this month, I read Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way and wrote a review with my thoughts on the book. I found it to be a great introduction to the structure of society in Ancient Greece and, of course, there were some references to the Gods. However, The Greek Way is not specifically intended to provide a comprehensive overview of the Gods and ancient mythology. Those topics are covered in Edith Hamilton’s Mythology which was first published in 1942. I purchased the 75th anniversary edition and was blown away with the elegant format and illustrations of this high quality hardcover.

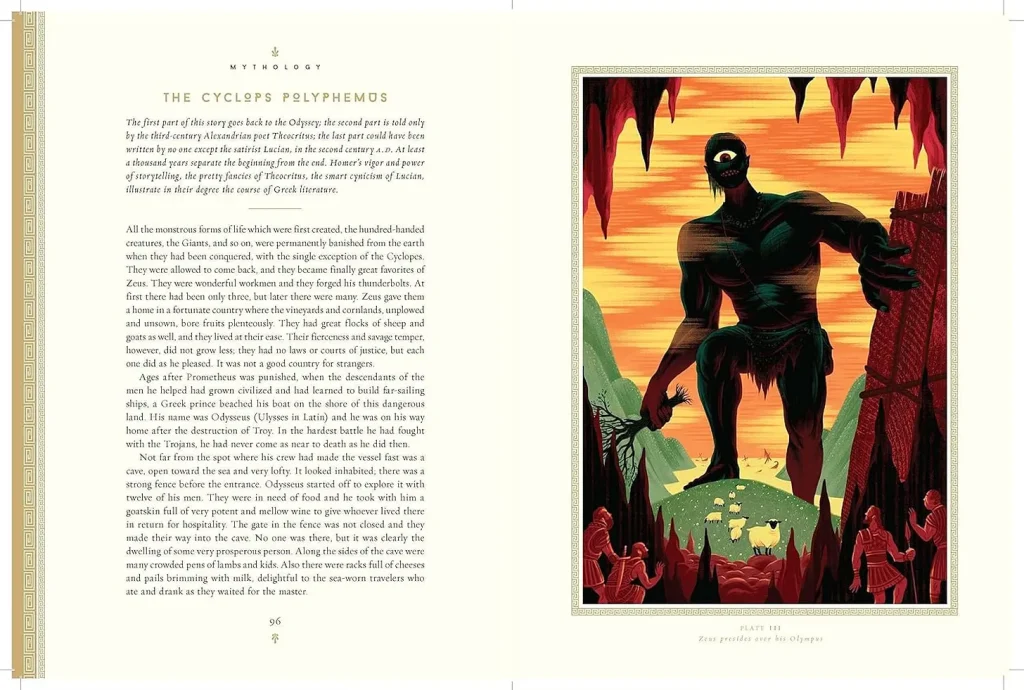

It is difficult to do justice to how beautifully presented this book is. I was expecting a simple book along the lines of The Greek Way rather than what I received. As an example of the book’s formatting and illustrations, take a look at these pages which introduce the famous story of Odysseus and the Cyclops:

This book is not a “Greek Bible” but it might be the closest thing we have to such a work, at least in a modern book that is meant for contemporary readers. Edith Hamilton, if she was alive today, might rebuke me for suggesting such a thing:

“Greek mythology is largely made up of stories about gods and goddesses, but it must not be read as a kind of Greek Bible, an account of the Greek religion. According to the most modern idea, a real myth has nothing to do with religion. It is an explanation of something in nature; how, for instance, any and everything in the universe came into existence: men, animals, this or that tree or flower, the sun, the moon, the stars, storms, eruptions, earthquakes, all that is and all that happens.”

So, in a sense, I am using the term “Greek Bible” loosely and perhaps inappropriately. But whatever we call these stories, they form a very important part of the ancient tradition and are referred to constantly in the literature of the period. In this way, I view the contents of Hamilton’s book to be akin to the Bible in terms of gaining a more comprehensive understanding of what I am reading.

I found the narrative to be delightful, especially when Hamilton summarizes famous stories by combining the accounts that appear in multiple sources. In many cases, famous stories are fragmented, with the account divided between historians, poets, and playwrights who lived centuries apart. What has come down to us today is only a sub-set of these traditions. Hamilton presents it all in a lively and entertaining way.

The book is divided into seven parts:

- The Gods, The Creation, and The Earliest Heroes

- Stories of Love and Adventure

- The Great Heroes Before the Trojan War

- The Heroes of the Trojan War

- The Great Families of Mythology

- The Less Important Myths

- The Mythology of the Norsemen

I found Part I to be the most useful for my purposes. Hamilton provides a detailed account of the twelve great Gods of Olympus, along with family trees depicting their relationships. She also provides both the Greek and Roman names of the Gods which is very useful. Most people know that Zeus and Jupiter represent the same God, but it is not easy to memorize the entire list. Each of the principal Gods is given a detailed explanation of their origin, powers, and their relationships to other Gods. These Gods do not resemble the God of the Bible. They have all-too-human emotions.

Hamilton does not stop with the principal Gods. We have briefer listings of the less important Gods who nonetheless are frequent characters in ancient literature. As I read through this part of the book, I was fascinated by the intricate relationships not only between the Gods but between Gods and mortal humans with whom they had relationships and often shared children — some immortal and some not.

For first-time readers of Homer, I think that Part III provides useful context as it discusses the heroes and legends that predated the Trojan War. Since many students are first exposed to this world in The Iliad and The Odyssey, reading Part I and Part III could serve as a jump start for better understanding. I see little downside to reading the first three parts of the book for those totally new to ancient literature.

Spoiler Alert!

Since I have read The Iliad, The Odyssey, and The Aeneid more than once in the past, I found Part IV fascinating. Hamilton provides her own concise summary of the Trojan War, using Homer as the primary source but also weaving in secondary sources to paint a fuller picture and to add context. She skillfully continues the story with her account of the adventures of Odysseus and Aeneas in the years after the Fall of Troy.

But I must caution the reader. Hamilton’s account gives away the plot of these classics! In fairness, her writing style and narrative assumes that her reader is familiar with these epics, and that’s probably the case for most people who pick up Mythology. However, for those who have never read Homer or Virgil, I hesitate to recommend reading Part IV before reading the epics. I recall being somewhat bewildered when I first read The Iliad, but I was enthralled with The Odyssey and, to a somewhat lesser extent, The Aeneid. I think it would have been a shame to know the plot in advance.

My recommendation is to read the first three parts of Mythology followed by Homer and Virgil, and then return to read the rest of what Hamilton has to say. This seems like the best of both worlds. I wish I had known more about the primary Gods prior to reading the epics, but I would not have wanted to know the entire story.

Modified Plan

After reading Mythology, I have decided to modify my original reading plan. I will return to The Iliad and The Odyssey for my next two books prior to proceeding with the reading lists of the Great Ideas Program. I am going to use a new translation of The Iliad by Emily Wilson. I have read her translation of The Odyssey before and will read it again. I might follow this with The Homeric Hymns.

I suspect that this modification to my plan will result in a greater appreciation for the playwrights of Ancient Greece. Their audience would have been intimately aware of the Greek Gods as well as the works of Homer. Virgil, of course, wrote The Aeneid several centuries later, so I will defer a re-reading of that epic for a later time.

I anticipate keeping Mythology on my coffee table as a reference as I proceed with my reading plans. If I encounter a God that seems bewildering, I can pick up Hamilton’s book to refresh my memory. This is a far better approach than resorting to Google or some AI bot that may or may not have much of a clue about Ancient Greek culture.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.