The folly of following markets on a daily basis

If you are a long-term investor, it is worse than pointless to update the quotes for your portfolio on a daily basis. There is simply too much day-to-day noise to make this exercise meaningful, as I recently observed in late April on a day when the S&P 500 traded down sharply:

Little did I know that I would soon have a great example of the futility of following markets on a daily basis. While the stock market was very volatile last week, if you zoom out and look at the week-over-week change, there was hardly any change at all:

The table below shows the daily changes in $SPY, which is an exchange traded fund that tracks the movements of the S&P 500:

Monday and Tuesday saw small gains and then the real action started on Wednesday afternoon when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell appeared to take a 75 basis point increase in the federal funds rate off the table for the June FOMC meeting. The ensuing party in the stock market lasted until the close but, alas, the party ended before Cinco de Mayo when a gloomy mood erased Wednesday’s gains and then some. This continued into Friday trading ending the week with another small decline.

I can understand why traders would follow all of this on a daily basis. After all, they are playing a different game and hoping to profit from just this sort of short-term market gyration. But for long-term investors, it makes no sense, and not just because it is a waste of time. By exposing ourselves to this noise, we increase the likelihood of making terrible emotionally driven mistakes.

Prospect Theory

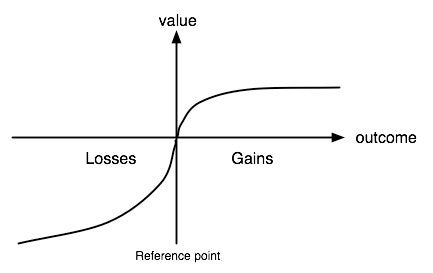

For several decades, it has been known that human beings view losses and gains in an asymmetric manner. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work on prospect theory shows that the pleasure we get from a gain of a certain amount is more than offset by a loss of that same amount.1

For example, if you find a $100 bill on the street, you will likely feel a rush of adrenaline and some pleasure from the fact that you just received a small windfall. You might think about what you’ll do with it, but you’ll probably just put it in your pocket and proceed with your day.

But let’s say that you were careless. You didn’t put the $100 bill in your wallet, but just into your pocket. Later on, you pull out your wallet for a $5 bill to pay for a coffee and the $100 bill you found earlier in the day mistakenly falls out of your pocket. Later on when you notice the loss, you will certainly be in a bad mood. Probably a very bad mood.

For most people, the net effect — the pleasure you get from finding the $100 bill less the pain of losing it — is a net negative overall effect. Your mental state is worse off than if you had never encountered that $100 bill to begin with even though your financial condition is no worse off.

What is true for that $100 bill is also true for securities quoted on a daily basis. If your stock portfolio goes up 3%, you’ll feel very good about it. But if it goes down 3% the next day, you’ll probably feel terrible … really terrible. In contrast, if you had not checked at all for two days, you’d see no net change and feel neutral.

The following chart illustrates the asymmetric effects described by prospect theory:

One other effect we can see is that the pleasure one gets from gains tends to flatten out at a certain point. The incremental pleasure we get from a 6% gain is not twice the pleasure we get from a 3% gain. In contrast, even small losses can cause a great deal of pain and more losses generate even more pain.

This is asymmetry that can cause us to make serious emotional errors.

Deprival-Superreaction Tendency

In one of his talks about the psychology of human misjudgment, Charlie Munger told the story of the Munger family dog who was normally very tame and good natured. The only time the dog would behave aggressively is if someone tried to take food out of its mouth. When the dog was deprived of something that he already possessed, he lost all ability to act rationally and bit his master’s hand.

Nothing could make less sense, even to a dog, than to bite the hand of his master. Except the dog’s psychology took over and caused irrational behavior due to what Charlie Munger calls deprival-superreaction tendency. Human beings share the psychology of dogs and other species when it comes to reacting to the loss of something we already possess or think we possess.

When the stock market rose on Wednesday after Jerome Powell’s soothing words, stocks went up 3% and someone following market moves on a daily basis put that 3% in the bank. The investor mentally took note of the gain and mentally possessed it.

The following day, the market gave up all of the gains and then some. What the investor thought he had gained suddenly evaporated, and all of the harmful psychology of loss aversion kicked in with a vengeance. This is prospect theory, loss aversion, and deprival-superreaction tendency in action. You probably didn’t bite anyone, but you might have mentally tortured yourself. And perhaps you even made some trades on Friday while being in a distressed mental state.

When I said that it is “worse than pointless” to update quotes on a daily basis, what I meant is that doing this is not some benign pastime for most people. We are messing with our all-too-flawed human psychology for no good reason.

Zoom Out

When you follow stock prices on a daily basis, you are essentially facing a coin-flip. Stocks are slightly more likely to go up than down on a daily basis, but barely. According to a study by Fisher Investments, stock returns have been positive on a daily basis 53% of the time.2

The following table should be examined carefully:

We can see that the percent of periods of positive daily returns is only 53.1% — essentially a coin flip. However, if we zoom out to a calendar month, 62.8% of periods are positive. For a calendar quarter, 68.8% of periods are positive, and 73.9% of calendar years are positive.

Consider the implications of this data given what we know about prospect theory and loss aversion. If you can resist following market quotes on a daily basis and instead update only every month, the percentage of time you will experience a negative outcome drops from 46.9% to 37.2%. And the negative experiences decline even further if you update quotes quarterly or annually.

If it is true that human beings perceive the pleasure of gains less intensely than the pain of an equivalent loss, you are guaranteed to face an aggregate mental toll if you look at quotes daily because you’re dealing with essentially a coin flip. But you stack the odds in favor of your mental health when you update quotes less often.

It is not merely a matter of mental health for sake of having a more pleasant life. Your financial outcome is likely to be materially worse when your mental state is negative because you could panic and make unwise investment choices. This is particularly true in bear markets when losses pile up.

Looking at quotes every day is like playing with fire. One day, you might snap and capitulate at the worst possible time.

I Don’t Zoom Out Enough

I’m aware of market quotes every day and typically update quotes in my portfolio spreadsheets on Friday evening.

This is too often, and I know it.

There is really no reason to update quotes more than monthly and that is what I should aim to do.

Fortunately, I do not know of any incident yet where I have made an emotional mistake due to excessive exposure to market quotes. Still, there is no reason to play with fire.

I’ve written about the dangers of anchoring to market quotes, yet I continue to be far too aware of quotes. So perhaps I am really writing this article more for my own benefit than yours.

- Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, covers prospect theory among many other fascinating topics related to psychology. I also recommend The Undoing Project which I reviewed several years ago. [↩]

- Historical Frequency of Positive Stock Returns by Fisher Investments uses daily data from January 31, 1928 to December 31, 2017. [↩]