Charlie Munger’s bet on enterprise software for court systems has been overshadowed by Daily Journal’s investment portfolio. The software business deserves more attention.

“The Company is not a smaller version of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Instead, it hopes to be a significant software company while it also operates its Traditional Business.”

— Daily Journal Corporation’s Fiscal 2022 10-K

Introduction

In March, Charlie Munger stepped down from his role as Chairman of Daily Journal Corporation after forty-five years. Mr. Munger remains a director focusing on the company’s large investment portfolio and I suspect that he will stay involved in strategic efforts to manage the long-term decline of the newspaper business while cultivating the enterprise software business known as Journal Technologies.

Daily Journal Corporation publishes ten newspapers that have suffered declining circulation during the early twenty-first century. Nine of the ten newspapers are over a century old, with the Los Angeles and San Francisco Daily Journals dating back to the late nineteenth century. The newspapers cater to specialized audiences, with the Daily Journals serving the legal profession and other titles targeting the real estate industry. With the exception of one paper operating in Arizona, all of Daily Journals newspapers operate in California.

To some degree, the niche market nature of the company’s newspapers has softened the blows that nearly all local newspapers have suffered in recent years. The Daily Journals accounted for 92% of total circulation revenues in fiscal 2022. While the company has been able to raise the regular subscription price at a 2% compounded rate over the past two decades, combined circulation of the Daily Journals has declined from 16,400 in fiscal 2002 to 5,640 in fiscal 2022.

Although circulation revenue has been on a nearly continuous slide for over two decades, Daily Journal enjoyed strong advertising revenue starting in 2007 due to a high volume of public notice advertising driven by foreclosures during the deflation of the housing bubble. Public notice advertising is required by law for foreclosures and Daily Journal was well positioned to capitalize. The advertising boom lasted until 2012.

Strong free cash flow during this period initially boosted the company’s holdings of treasury securities. Starting in 2009, Mr. Munger began buying equity securities. By 2011, investors familiar with Mr. Munger’s role at Berkshire Hathaway were attracted to Daily Journal because it seemed like it was becoming his investment vehicle.

In 2011, I wrote Daily Journal Corporation: Declining Publisher or Rising Hedge Fund? which provided more background information on the state of the newspaper business and Mr. Munger’s investment activities. In 2016, I wrote a follow up article: Revisiting Daily Journal Corporation – Five Years Later. Readers who are interested in more data and historical context should find those earlier articles useful.

Earlier this month, Daily Journal’s latest 10-K was released for the fiscal year that ended on September 30, 2022. As I seem to do every year during the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day, I spent some time reading the company’s relatively brief 10-K and updated my spreadsheets going back over two decades.

Daily Journal might be a candidate for a business profile next year, but a full description of recent results is not the topic for today’s article. Instead, I have some general thoughts to share regarding Daily Journal’s activities in the software industry. This article does not contain a financial analysis of Journal Technologies but instead offers mostly qualitative thoughts on the software industry in general.

Journal Technologies develops “vertical market software” — in their case targeting the courts and justice systems. I am very familiar with vertical market software due to many years spent in a similar software business targeting a different vertical market. Given that background, I thought it would be interesting to share my views on the vertical market software industry in general, and as it applies to Journal Technologies.

Prior to the paywall, I thought it would be appropriate to provide links to the Daily Journal annual meeting transcripts for the past several years which have been posted by Latticework Investing. These transcripts are excellent resources for those who are interested in learning more about the company.

Daily Journal Annual Meeting Transcripts: 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022

Now, let’s take a look at the vertical market software industry.

Vertical Market Software

Vertical market software serves organizations that operate in a specific industry with highly specialized requirements. In the case of Journal Technologies, the company builds software designed to handle the needs of the justice system and the courts. However, there are countless other vertical markets that have specialized needs.

For over a decade, I was involved in building enterprise software for membership-based organizations such as trade associations, membership societies, and unions. Such organizations have specific requirements related to membership management that are not available in “horizontal” software products that target organizations across multiple industries. In many cases, membership-based organizations have unique workflows and extensive customization requirements.

Whether the vertical market is the court system or membership-based organizations, software serving such markets has historically been very expensive and inflexible. For those of us who are used to the very latest in modern technology in our work and personal lives, it can be shocking to realize that many large organizations are still using technology that is often decades old. Many antiquated systems are either entirely custom built for a specific organization or are heavily modified software products that can no longer be upgraded effectively. In either case, long established workflows and habits militate against adoption of modern software.

Tyler Technologies, one of Journal Technology’s most important competitors, estimates that two-thirds of its target market are organizations with homegrown or custom systems that are over twenty years old and coded in COBOL, a programming language that is much less flexible than modern languages.

The antiquated nature of software in government agencies does not surprise me. Many of the membership association customers that I interacted with in the 1990s and 2000s were running software that deployed in the 1970s and 1980s. I would not be at all surprised if software that I installed in the 2000s is still in production today. Organizations are slow to change and once software is installed, it tends to be sticky.

Technological Change

As Tyler Technologies mentioned in their presentation, many legacy systems were built using COBOL which traditionally ran on mainframe computers with primitive character-based user interfaces that predate the Windows and Macintosh operating systems. Many of the systems that I replaced with Windows-based software in the 1990s and 2000s were legacy character-based mainframe systems.

Legacy systems were typically homegrown custom systems or software packages that were heavily customized to fit the business requirements of the client. Custom legacy systems are the most expensive to maintain and the least flexible, often requiring the services of individual employees who understand codebases that are usually poorly documented. When longtime employees resign or retire, organizations are often left with systems that cannot be modified or maintained.

Modifying legacy commercial software products is often not much better than dealing with completely custom systems. Legacy software was often customized by modifying the commercial software in ways that made upgrades difficult. As a result, many organizations ended up running commercial software that was obsolete and could not take advantage of updates released by the software vendor without redoing all of their custom work and dealing with bugs that invariably would arise.

The rise of object oriented software and client-server systems represented a major advance over legacy systems. Rather than delivering a monolithic codebase to customers who would modify it in ways that impeded future upgrades, software companies could deliver products that were highly customizable and upgradable. Users enjoyed the productivity gains of a graphical user interface and information technology departments could be more responsive to changing requirements.

While the client-server systems deployed during the 2000s were far more flexible than their predecessors, for the most part the systems were still deployed on-premise at client locations. As a result, organizations had to maintain these systems or hire consultants to do so. In addition, many such systems were not natively available online and e-commerce “add-ons” were needed to expose functionality to the web.

Over the past decade, the software landscape has again shifted with client-server systems being supplanted by software solutions that can be deployed “in the cloud”. Amazon Web Services and other hosted platforms offer organizations the ability to outsource the responsibility of maintaining server platforms on their own premises, although some larger organizations may still elect to run their own server operations.

Software as a Service (SAAS)

The traditional business model in enterprise software involved selling perpetual software licenses to clients that allow for the installation and use of the software indefinitely. In addition, software companies sell annual maintenance packages which typically provide clients with upgrades to the software as well as varying levels of ongoing support. In the membership-based vertical market, it was not unusual for perpetual licenses to run well into the six figures. Annual maintenance was typically 20-25% of the cost of the license and nearly all clients elected to pay for maintenance.

With the rise of cloud computing, the software business model underwent massive changes starting in the late 2000s. Customers would no longer purchase perpetual licenses to install software on their own premises nor would they pay annual maintenance. Instead, clients would pay an annual subscription fee in exchange for the right to use the software as an ongoing service (SAAS). In addition, clients could elect to pay additional fees to have the software hosted by a third party.

In both the traditional and SAAS models, clients would usually pay consulting fees to software vendors in exchange for making customizations to meet specific business needs, handle data conversions, and to train end users. In my experience, it was not unusual for consulting fees to approach the cost of the perpetual license and to last several months or, in very complicated cases, up to a year, before customers “went live” with the software for production use.

The economics of the traditional model could be extremely lucrative. Once a software product is built, the incremental costs of selling an additional perpetual license was close to zero which provided for extremely high margins on license sales. Annual maintenance revenue is also generally high margin, although there are costs associated with providing bug fixes and upgrades. Consulting services are lower margin given that employees must be dedicated to specific clients projects, although in my experience, consulting rates still offered attractive economics.

The SAAS model upended the traditional business model by eliminating the initial sale of perpetual licensing revenue. Instead, the annual subscription revenue would replace both the perpetual license and annual maintenance revenue streams. While this reduced revenue in the short term, it held the potential for longer client lifetime revenue depending on the price of annual subscriptions.

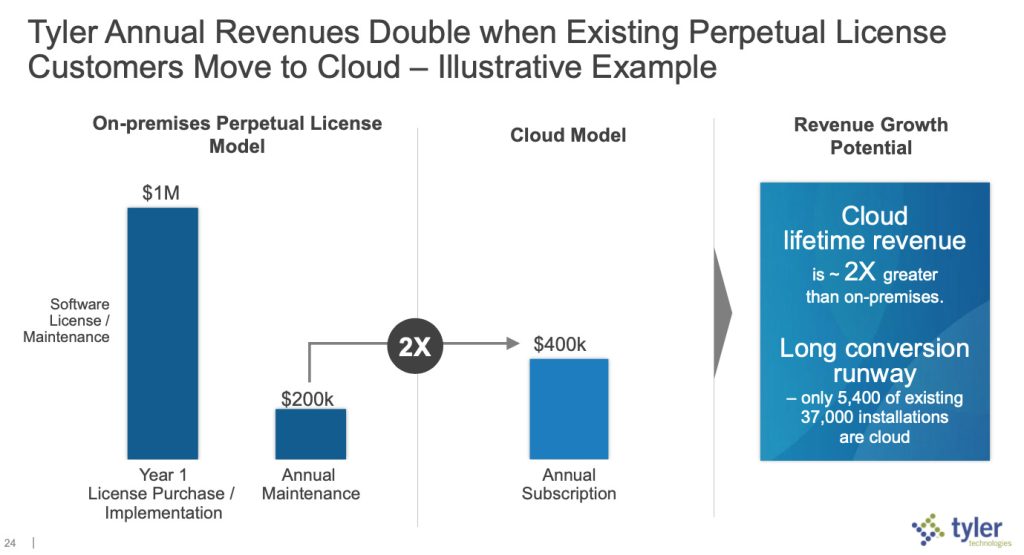

I left the software industry in 2009 around the time the SAAS model was gaining steam, so my personal exposure to the economics of SAAS vs. the traditional model is limited. However, I found this slide from Tyler Technologies interesting because it illustrates a path toward greater lifetime revenue under the SAAS/Cloud model:

The left side of the presentation represents the economics of the traditional model while the right side illustrates the SAAS cloud based model. The numbers provided for the perpetual license model are quite similar to what I recall from the mid to late 2000s. The cloud model obviously has the potential to deliver greater revenue over long periods of time but this depends on client retention.

Building Partnerships

“… You can argue that the little old Daily Journal, what a good thing it was we had 30 million extra coming in from a foreclosure boom and that we invested it shrewdly. It gives us a lot of flexibility. And by the way, that piled up money helps us in wooing these governmental bodies who we are selling the software to. We look more responsible with the extra wealth, and we are more responsible with the extra wealth.”

— Charlie Munger, 2022 Daily Journal Annual Meeting

The sales cycle for enterprise software is long, winding, and complex. An entire industry has been built around developing requests for proposals (RFPs) that help clients define their business needs clearly. Developing an RFP can take several months and such documents can be hundreds of pages long. Clients then submit the RFP to the top vendors offering software in their particular vertical market and it can take a sales team weeks to adequately complete an RFP response. By the time demos are scheduled, both the client and the software company have spent a considerable amount of time on the process. The RFP process, sales demonstrations, and financial negotiations can take months to complete.

The process takes a long time because the stakes are extremely high, both for the client and for the software company. Buying enterprise software can be tremendously disruptive for an organization and botched implementations can end careers. It is absolutely essential for an organization to fully vet software companies to ensure that they not only have the best solution but also are in a position to offer the consulting services needed to implement customizations and that they have the financial stability to remain in business for years and decades to come.

As Charlie Munger noted in the quote presented above, the court and justice systems that are shopping for software are very interested in the financial stability of vendors. The fact that Daily Journal has amassed a large portfolio of securities provides Journal Technologies with credibility. Just from a financial standpoint, it is obvious that the company has staying power. In addition, Charlie Munger’s presence on the board and the corporate ethos he represents provides additional confidence.

While buying a subscription to software on the Apple or Google app stores might be like “dating”, enterprise software is more like “marriage”, both in terms of the cost of the decision and the length of the relationship. A major part of the RFP and sales process is to help the client get comfortable with the vendor. Charlie Munger’s comments about the process at the 2022 annual meeting seem very familiar to me:

“What there is a huge market for the automation of the courts, and it’s early. That’s the good news. It’s a big market and the bad news is it’s a slow damn tough way to grind ahead in software because it’s very bureaucratic…RFP, Government bodies. It’s a huge market, and it’s intrinsically going to be very slow to get done. That’s the good news and bad news, we have a huge market and it’s going to be slow and bureaucratic. There isn’t any doubt about what’s going to happen, the courts are going to get more efficient and get with the modern world. And also the district attorney’s offices and the probation offices.”

In addition to Daily Journal’s strong financial position, the company also has a very long history in the legal profession. The Los Angeles and San Francisco Daily Journals have been declining but are still read by thousands of lawyers and judges throughout California. I suspect that the readership of these flagship publications is on the older side and occupies positions of decision making authority. It is quite likely that the government officials making software purchase decisions in California are readers of the Daily Journal. This reputational benefit most likely extends well beyond California.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is not to delve into the financial performance of Journal Technologies but rather to provide some perspective on the software industry in general and vertical market software in particular. I think that it is also worth considering Charlie Munger’s personality and the business ethos he embodies when he often discusses a “seamless web of deserved trust”.

From Mr. Munger’s perspective, it is clear that both the traditional publishing business and the software business represent public trusts and that he enjoys playing a constructive role by delivering value to customers and society.

Consider this quote from the 2020 annual meeting:

“I’ve fallen in love with the government of Australia. They’re just such nice people and I think it’s wonderful that Australia wants automated courts. And I think it’s wonderful they’re smart enough to hire us. Imagine hiring the little Daily Journal Company to run the courts of Australia. And my guess is it’s all going to work for them and for us. It’s a miracle they figured out that this little company would be a pretty safe choice. I think part of the reason we’ve been successful is so many of our competitors are so awful. So we don’t deserve as much credit as we’re claiming.”

I can relate to these sentiments. Many of the clients that I dealt with during my software career were nonprofits with worthwhile missions and I was motivated to do a good job because I wanted them to succeed. Of course, the same should be true regardless of the industry or the type of product involved. In the long run, it is difficult to build a successful and profitable business if you have unhappy customers who feel like they are not receiving value for their money.

It appears that Tyler Technologies is Daily Journal’s main competitor in the court and justice system vertical markets. Tyler is a much larger business and it is publicly traded. I have done some cursory reading about Tyler but do not know the company well enough at this point to opine on the competitive landscape. I find it intriguing that Mr. Munger characterized the competition as “awful”, and perhaps this provides an opening for Journal Technologies.

Investors tend to focus on Mr. Munger’s activities in securities because the size of the investment portfolio makes it the most important component of value for Daily Journal. While I would not argue with those who focus mostly on the investments, it seems worthwhile to get to know the software business as well given the generous valuations multiples that the market usually assigns and the potential for the business to be sold or spun off at some point in the future.

Copyright and Disclaimer

This newsletter is not investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

No position in Daily Journal Corporation.