In Today’s Issue:

- My $2 Million Apple Mistake

- Jim Lehrer, 1934-2020

- Coronavirus and The Precautionary Principle

- Goodwill Accounting

To read last week’s newsletter about Farnam Street’s Great Mental Models book, Morgan Housel’s interview of Brent Beshore, and Getting in on the 50th Floor, please click here.

My $2 Million Apple Mistake

“It was Thanksgiving weekend. I had been watching Apple for a couple of months. The stock was pummeled on soft results in September and seemed cheap. On Sunday night, I looked at the Value Line report and on Monday I reviewed the latest financial statements. On Tuesday morning, I pulled the trigger. I was now the proud owner of 500 shares of Apple purchased at $18.”

For three months from late November 2000 to early March 2001, I was an Apple shareholder. Trading Apple seemed smart at the time but, in hindsight, the fact that I did not hold those shares for the long haul carried a severe opportunity cost. Was the decision a good one based on the information then at my disposal? Or was it a foreseeable debacle that should have been avoided?

For reasons that I can only reconstruct at this point since I did not maintain a decision journal at the time, I sold Apple in March 2001 and used the proceeds to purchase Berkshire Hathaway. I still own those Berkshire shares today and they have returned an annualized 9.3% over nearly 19 years, but of course that pales in comparison to “what could have been” with Apple. Read the full story which was published on The Rational Walk this week.

Jim Lehrer, 1934 – 2020

PBS NewsHour co-founder Jim Lehrer died on January 23 at the age of 85. Lehrer was well known as a straight shooter and, to this day, I am not certain about his personal political beliefs, which is as it should be for a hard news journalist. Lehrer had nine rules for journalists:

- Do nothing I cannot defend.

- Cover, write and present every story with the care I would want if the story were about me.

- Assume there is at least one other side or version to every story.

- Assume the viewer is as smart and caring and good a person as I am.

- Assume the same about all people on whom I report.

- Assume personal lives are a private matter until a legitimate turn in the story absolutely mandates otherwise.

- Carefully separate opinion and analysis from straight news stories and clearly label everything.

- Do not use anonymous sources or blind quotes except on rare and monumental occasions. No one should be allowed to attack another anonymously.

- “I am not in the entertainment business.”

Needless to say, the majority of broadcast journalism today falls into the “entertainment” category and is driven primarily by ratings. Opinion and hard news journalism is often hard to distinguish. I haven’t owned a television or paid much attention to broadcast news on the internet for many years because Jim Lehrer’s style of journalism no longer seems to exist. The video below was released by PBS to commemorate his life.

Coronavirus and The Precautionary Principle

The outbreak of a new strain of coronavirus has been in the news over the past week. The source of the outbreak has been traced to Wuhan, China and has spread to several distant countries including the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, all of the cases in the United States as of January 27 involved people who acquired the illness abroad and there has been no person-to-person transmission of the virus within the United States.

Most coronaviruses are not life threatening for humans, but certain new strains have caused havoc in the past. In 2003, 774 people died from SARS, a type of coronavirus that also originated in China. Humanity has always dealt with contagious diseases but for almost all of human history, no person could travel faster than the speed of a horse. Modern aviation took off in the post World War II era and became affordable to hundreds of millions of people only relatively recently. The prospect of a pandemic spreading like wildfire naturally worries people given that an infected person can travel to the other side of the world in less than 24 hours.

What is the appropriate balance between preventing the potential spread of an infectious disease and avoiding unnecessary overreactions that could harm the economy and constrain human liberty? Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of the Incerto series of books, has built a reputation in the field of risk management. Taleb’s precautionary principle counsels policymakers to use extreme caution when facing scenarios involving a risk of ruin:

“The precautionary principle (PP) states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing severe harm to the public domain (affecting general health or the environment globally), the action should not be taken in the absence of scientific near-certainty about its safety. Under these conditions, the burden of proof about absence of harm falls on those proposing an action, not those opposing it. PP is intended to deal with uncertainty and risk in cases where the absence of evidence and the incompleteness of scientific knowledge carries profound implications and in the presence of risks of “black swans”, unforeseen and unforeseeable events of extreme consequence.”

Taleb has weighed in on the current coronavirus situation on Twitter as well as in a brief paper. Taleb argues that constraining mobility during the early stages of a potential pandemic is the only approach that makes sense in light of the advances in global connectivity and the resulting ability of viruses to spread extremely rapidly in a manner that would not have been possible in the past. Taleb acknowledges that this approach will cost something but failing to do so will “eventually cost everything – if not from this event, then one in the future.”

Chances are that even if Taleb’s policy prescription is not adopted for this particular situation, humanity will survive with minimal damage. His point, however, is broader than that. If we repeatedly take similar gambles with inadequate policy in the future, at some point we could be faced with a pandemic that cannot be stopped before it takes an unimaginable number of human lives.

Goodwill Accounting

Chick-fil-A has grown into one of the largest fast food restaurants in the United States with over 2,300 restaurants in 47 states and $3 billion in annual revenue. Financial information is hard to come by because the company has been held privately by the Cathy family since its founding in 1946 and it reportedly will never go public, although it is possible that it could be acquired.

If a company like Chick-fil-A is ever acquired, the valuation is likely to be quite high given its growth profile. The price an acquirer would have to pay would far exceed the net tangible assets on the company’s balance sheet. Why is this the case? The answer is straight forward: It would not be possible to replicate Chick-fil-A if someone attempts to build it from scratch by just investing an amount equivalent to the company’s tangible capital. Any acquirer would have to pay a significant premium above book value in recognition of the intangible assets, namely the brand identity and the unique culture of service embodied by the firm’s management.

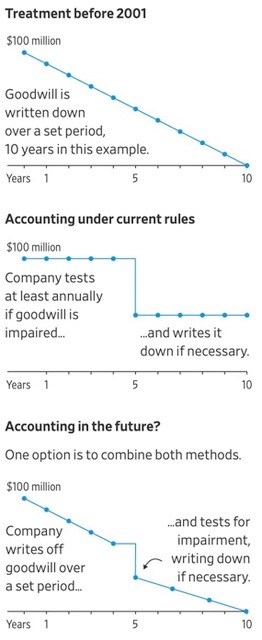

When a company is acquired for an amount in excess of its book value, the acquiring company must create an asset on its balance sheet to track the “goodwill” that has been paid. Prior to 2001, this goodwill asset would be amortized, or written off, against annual earnings over a forty year period. After 2001, goodwill was not required to be written off annually but had to be “tested” every year for impairment.

Both approaches have serious limitations and do not necessarily reflect the ongoing value of intangibles such as brand and culture. The Wall Street Journal recently published an article outlining the proposed changes and their implications. The illustration below was included in the article and contrasts the treatment of goodwill prior to 2001 with the current and proposed treatment.

There is no perfect way to account for goodwill. Amortizing goodwill against earnings over a fixed period such as forty years might make no sense if economic goodwill is actually increasing over time, as it ideally would when building and maintaining a brand. However, giving management the latitude to determine goodwill impairments annually could delay the recognition of damage to economic goodwill. It should also be noted that economic goodwill can never be written up on a balance sheet. This creates a problematic and asymmetric scenario.

Ultimately, security analysts cannot take the goodwill line item on balance sheets very seriously and must make an independent assessment of the economic goodwill of a business. We will be following this story as the accounting rule changes are finalized.

That’s all for this week. The next issue of Rational Reflections will be sent out on Wednesday, February 5. Any feedback is welcome and can be sent to administrator@rationalwalk.com. Thanks for subscribing!

Was this email forwarded to you by a friend or colleague? Sign up here to receive Rational Reflections directly every week.

Copyright and Disclosures

Nothing in this newsletter constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.