Note to Readers: The following essay is part of an introductory section of The Rational Walk’s widely acclaimed Berkshire Hathaway Briefing Book which was published on February 28, 2010.

For a formatted PDF File of the following essay, please click on this link.

From Cigar Butts to Business Supermodels

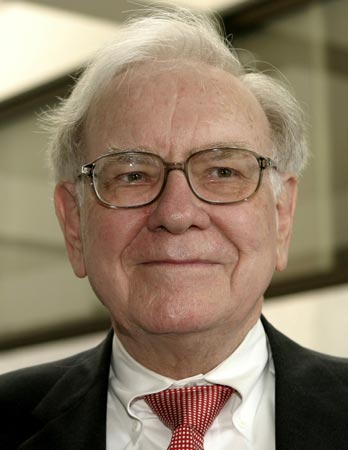

There are numerous books and publications that provide detailed accounts of the history of Berkshire Hathaway as well as Warren Buffett’s life and career. It is also impossible to fully understand Berkshire without studying the life and career of Vice Chairman Charles T. Munger. A list of resources for those interested in a comprehensive history of the company and its leaders is provided as an appendix to this document (available in the forthcoming full analysis). This section merely attempts to provide some context regarding the remarkable history of Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett’s investment approach.

There are numerous books and publications that provide detailed accounts of the history of Berkshire Hathaway as well as Warren Buffett’s life and career. It is also impossible to fully understand Berkshire without studying the life and career of Vice Chairman Charles T. Munger. A list of resources for those interested in a comprehensive history of the company and its leaders is provided as an appendix to this document (available in the forthcoming full analysis). This section merely attempts to provide some context regarding the remarkable history of Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett’s investment approach.

Warren Buffett’s Early Investment Philosophy

Warren Buffett’s early investment philosophy was largely based on the principles developed by Benjamin Graham. Mr. Buffett has stated on many occasions[1] that his view of investing changed dramatically when he first read Mr. Graham’s book, The Intelligent Investor, in early 1950. Up to that point, Mr. Buffett had read every book on investing available at the Omaha public library but none were as compelling as Mr. Graham’s straight forward approach summarized in the phrase: “Margin of Safety”.

Warren Buffett’s early investment philosophy was largely based on the principles developed by Benjamin Graham. Mr. Buffett has stated on many occasions[1] that his view of investing changed dramatically when he first read Mr. Graham’s book, The Intelligent Investor, in early 1950. Up to that point, Mr. Buffett had read every book on investing available at the Omaha public library but none were as compelling as Mr. Graham’s straight forward approach summarized in the phrase: “Margin of Safety”.

Benjamin Graham’s approach is more fully documented in Security Analysis which, in contrast to The Intelligent Investor, is more targeted toward professional investors. Mr. Graham’s approach involved examining securities from a quantitative perspective and making purchases only when downside risks are minimized. This approach rarely involved speaking to management since doing so could adversely influence the analyst’s impartial view of the data. In particular, Mr. Graham was a proponent of purchasing stocks selling well under “net-net current asset value” arrived at by taking a company’s current assets and subtracting all liabilities. In such cases, the buyer was paying nothing for the business as a going concern and had some downside protection due to liquid assets far in excess of all liabilities.

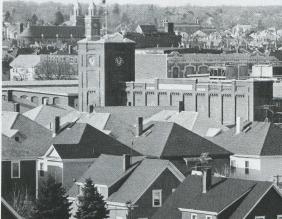

Mr. Buffett was able to leverage the “deep value” approach advocated by Benjamin Graham throughout the 1950s. In the five year period ending in 1961, the Buffett Partnerships trounced the Dow Jones Industrial average with a cumulative return of 251 percent compared to 74.3 percent for the Dow[2]. While Mr. Buffett employed multiple strategies, one approach involved finding companies that fit the “cigar butt” mold, meaning that they had “one puff left” and could be purchased at a deep bargain price. This approach led Mr. Buffett to begin acquiring shares of Berkshire Hathaway, a struggling New England textile manufacturer, in late 1962. While Berkshire Hathaway was trading well under book value at the time, Mr. Buffett would later say that book value “considerably overstated” intrinsic value[3].

Mr. Buffett was able to leverage the “deep value” approach advocated by Benjamin Graham throughout the 1950s. In the five year period ending in 1961, the Buffett Partnerships trounced the Dow Jones Industrial average with a cumulative return of 251 percent compared to 74.3 percent for the Dow[2]. While Mr. Buffett employed multiple strategies, one approach involved finding companies that fit the “cigar butt” mold, meaning that they had “one puff left” and could be purchased at a deep bargain price. This approach led Mr. Buffett to begin acquiring shares of Berkshire Hathaway, a struggling New England textile manufacturer, in late 1962. While Berkshire Hathaway was trading well under book value at the time, Mr. Buffett would later say that book value “considerably overstated” intrinsic value[3].

From Cigar Butts to Insurance

Berkshire Hathaway, as it existed in 1963 when the Buffett Partnership became the company’s largest shareholder, was a cheap company from a quantitative perspective but it was not a good company in terms of offering a business that had durable competitive advantages. In fact, over the next two decades, Berkshire Hathaway continued to invest in the textile mills but would never gain sufficient traction to complete with overseas competitors with lower cost structures. Textiles are a commodity business and the low price producer has the advantage. In retrospect, Mr. Buffett’s purchase of Berkshire Hathaway was a mistake[4].

While Berkshire’s textile mills were doomed to eventual failure, a period of profitability[5] appeared in the mid to late 1960s that presented Mr. Buffett with a choice: He could either reinvest the profits in the textile business or redeploy the funds elsewhere. Above all else, Mr. Buffett is a master capital allocator. He could see the troubles brewing in textiles and, despite attempts by Berkshire’s textile managers to obtain capital for new investments, Mr. Buffett chose to deploy the funds elsewhere.

Berkshire’s entry into the insurance business with the purchase of National Indemnity in 1967[6] was a transformational event for the company. The textile business, despite a temporary period of profitability, required significant capital investments to continue to remain competitive. In contrast, insurance operations that are well run generate significant cash in the form of “float”. Float represents funds that are held by an insurance business between the time when policyholders submit payment and when funds are eventually paid out to settle claims. As long as underwriting practices are sound, float represents a low cost means of funding investments. By purchasing National Indemnity, Berkshire was on its way to transforming from a textile manufacturer consuming large amounts of capital at low to negative rates of return into an insurance powerhouse generating large amounts of float for investment in other businesses offering better prospects of high returns.

See’s Candies: The Turning Point

Few Californians can recall a holiday season where See’s Candies were not a prominent part of the festivities. The brand is so powerful in California and other western states that many consumers would never think of buying a competing product. See’s Candies is a textbook example of a company with a formidable “moat”. Such companies have built up brand identity that cannot be replicated by new entrants even with significant capital investments[7].

Few Californians can recall a holiday season where See’s Candies were not a prominent part of the festivities. The brand is so powerful in California and other western states that many consumers would never think of buying a competing product. See’s Candies is a textbook example of a company with a formidable “moat”. Such companies have built up brand identity that cannot be replicated by new entrants even with significant capital investments[7].

Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman Charles Munger has been widely credited with convincing Warren Buffett that there are certain situations where deviating from Benjamin Graham’s “deep value” approach can be justified. Mr. Munger has rebutted[8] the notion that his influence was a deciding factor in Mr. Buffett’s overall record, but many accounts[9] of the events surrounding the See’s Candies purchase supports the conclusion that Charlie Munger deserves much credit for shifting Berkshire’s bias from cigar butts selling at a “bargain price” to excellent businesses selling at a “fair price”.

Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman Charles Munger has been widely credited with convincing Warren Buffett that there are certain situations where deviating from Benjamin Graham’s “deep value” approach can be justified. Mr. Munger has rebutted[8] the notion that his influence was a deciding factor in Mr. Buffett’s overall record, but many accounts[9] of the events surrounding the See’s Candies purchase supports the conclusion that Charlie Munger deserves much credit for shifting Berkshire’s bias from cigar butts selling at a “bargain price” to excellent businesses selling at a “fair price”.

See’s Candies is the perfect example of a business that produces an excellent return on equity year after year but requires very little capital investment in order to sustain the “moat” that makes such returns possible. When Berkshire purchased See’s Candies for $25 million in 1972, the company only had $8 million of net tangible assets. However, See’s was earning approximately $2 million after tax at the time[10]. $17 million of the $25 million purchase price could not be accounted for by assets on See’s balance sheet but represented the value represented by intangible “brand equity”.

Over the first twenty years of Berkshire’s ownership of See’s Candies, sales increased from $29 million to $196 million while pre-tax profits grew from $4.2 million to $42.4 million. However, that is not even the most amazing part of the story. What is more remarkable is that Berkshire Hathaway only had to reinvest $18 million of retained earnings over that twenty year period while $410 million of cumulative pre-tax earnings were sent back to Berkshire for redeployment in other investments[11].

There have been many other key turning points in the history of Berkshire Hathaway but the decision to pay a “premium price” for See Candies in 1972 may best symbolize the transformation of Mr. Buffett’s approach toward investing. This is perfectly summarized in Mr. Buffett’s 1992 Letter to Shareholders:

In my early days as a manager I, too, dated a few toads. They were cheap dates – I’ve never been much of a sport – but my results matched those of acquirers who courted higher-priced toads. I kissed and they croaked.

After several failures of this type, I finally remembered some useful advice I once got from a golf pro (who, like all pros who have had anything to do with my game, wishes to remain anonymous). Said the pro: “Practice doesn’t make perfect; practice makes permanent.” And thereafter I revised my strategy and tried to buy good businesses at fair prices rather than fair businesses at good prices.

Berkshire Hathaway is the company it is today because Mr. Buffett stopped kissing toads like the original Berkshire textile business and started aggressively pursuing supermodels like See’s Candies instead even if they were more “expensive dates”. As we shall see, Berkshire has no shortage of supermodels today.

Footnotes:

[1] For example, see Mr. Buffett’s preface to any recent edition of The Intelligent Investor.

[2] The Buffett Partnership track record is available in many publications. See, for example, Roger Lowenstein’s Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist, 1995 Hardcover Edition, Page 69.

[3] See comment in Berkshire Hathaway Owner’s Manual, Page 5.

[4] Mr. Buffett directly stated that buying Berkshire was a mistake in his 1989 letter to shareholders.

[5] See Lowenstein, Page 133.

[6] For a good history of the National Indemnity purchase, see Lowenstein, pages 133 to 135.

[7] For an excellent brief history of See’s Candies, see Max Olson’s paper entitled Quality without Compromise.

[8] See Mr. Munger’s statement in Poor Charlie’s Almanack, Third Edition, “Rebuttal: Munger on Buffett”

[9] For example, see Alice Schroeder’s account of the See’s Candies purchase in Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, Chapter 34.

[10] See the appendix to Warren Buffett’s 1983 Letter to Shareholders.

[11] See Warren Buffett’s 1991 Letter to Shareholders.

Disclosure: The author owns shares of Berkshire Hathaway.