Introduction

Let’s put ourselves in Warren Buffett’s shoes on Friday, February 25, 2022.

Mr. Buffett’s annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders was scheduled to be posted on the internet the next morning.1 From a capital allocation perspective, the most important news in the letter was that Berkshire continued to repurchase shares in 2021. Over the course of two years, Berkshire deployed $51.7 billion to repurchase 9% of the shares that were outstanding at the end of 2019.

Berkshire Hathaway shares were clearly attractive from Mr. Buffett’s perspective, but he would have almost certainly preferred to find companies to acquire at the right price. Unfortunately, such opportunities were not found in 2021.

We can picture Mr. Buffett in his office in Omaha thinking about his annual letter and mulling over the potential of acquiring one of the countless public companies that he has been following for many years or even decades.

On his desk, Mr. Buffett picks up a letter from Joe Brandon, the newly appointed CEO of Alleghany, along with the company’s annual report. He starts reading. Since he’s closely observed the company for decades, it is likely that it didn’t take him very long to review the report. Perhaps he writes down a few figures, but most of the math is done in his head. He’s convinced that a deal to acquire Alleghany could make sense and picks up the phone to arrange a meeting with Joe Brandon.

Of course, I’m taking some liberties regarding what took place, but we do know that the phone call happened on February 25 based on Alleghany’s preliminary proxy statement which has a section outlining the events that occurred between that phone call and the announcement of the deal on March 21. My article on the day of the announcement considered what might have motivated Mr. Buffett to make an offer.

Was Alleghany the only company Mr. Buffett considered in late February?

This seems impossible to believe. If he was looking at Alleghany as an acquisition candidate, it seems obvious that he was also considering other insurance companies.

It is possible that Mr. Buffett reviewed Markel Corporation’s 2021 10-K which had been released a week earlier. Both Alleghany and Markel have long histories of profitable insurance operations, and both have a collection of non-insurance subsidiaries. Both are often regarded as “mini-Berkshires”.

Assuming that both companies were on Mr. Buffett’s radar, what might have made him more interested in acquiring Alleghany rather than Markel?

Before delving into the specifics of Markel and Alleghany, let’s examine the idea of creating a “mini-Berkshire” — that is, a company operating at smaller scale that is attempting to emulate Berkshire’s strategy. Then, let’s consider what would make Mr. Buffett interested in acquiring such a company.

Building a “Mini-Berkshire”

Berkshire Hathaway stock compounded at a 20.1% annual rate between 1965 and 2021, a record so extreme as to guarantee that many companies will try to emulate the strategy that led to this success. Berkshire’s early days are now well documented and there is a roadmap that anyone can study and attempt to follow.2

Shortly after taking control of Berkshire Hathaway, Mr. Buffett entered the insurance industry with the purchase of National Indemnity in 1967. The basic business model of an insurance company involves collecting premiums from policyholders to cover various risks and to earn investment income from the resulting float.

Float represents funds that are held by an insurer between the time when policy holders submit payment and when funds are eventually paid out to settle claims. Due to regulatory reasons, most insurers invest float primarily in fixed income securities and typically attempt to match the duration of the fixed income portfolio to the timing of payments to policyholders. Regulation of insurance companies is intended to protect policyholders rather than shareholders. Float invested in fixed income securities is viewed by regulators as safer than investments in common stocks or non-insurance operating subsidiaries.

With sufficient capital strength, an insurer can begin to move beyond fixed income securities into common stocks and the ownership of entire businesses. This is precisely what Berkshire Hathaway did over several decades. The world has changed dramatically over the past half century, but the road map of Berkshire’s early history has encouraged a few smaller insurers to adopt some of Mr. Buffett’s early strategies.

With a market capitalization of over $750 billion, Berkshire is far too large for small acquisitions to make sense. The following acquisition criteria was published by Berkshire Hathaway in the company’s 2017 annual report. The figures have not been updated since then, and it is likely that the minimum criteria are higher today:

Every element of Berkshire’s acquisition strategy could be emulated without the risk of competing with Berkshire itself for acquisitions under the $5 billion minimum. One of Warren Buffett’s specialties has been to acquire companies run by founders or the families of founders who wish to obtain liquidity or diversification but love their business and intend to keep running it. The attraction of selling to Berkshire rather than going public or selling to a private equity firm mainly interested in “flipping” the business after a few years has appealed to certain family-run companies and provided a competitive advantage for Berkshire.

Suppose that you are the grandson of the founder of a manufacturing business that has a potential market value of $1 billion. You could send your financial statements and a letter to Warren Buffett but unless he thinks that your business could be a “bolt-on” acquisition for one of Berkshire’s existing subsidiaries, he isn’t going to be interested because the purchase is not large enough to “move the needle” of his $750 billion conglomerate. You could go public or set up a private equity auction, but you want to continue running the business and care about the future of your employees.

What are you going to do?

One viable option is to contact one of the “mini-Berkshires” that have demonstrated an interest in emulating Berkshire Hathaway and have a track record proving that they buy and hold family-run businesses for the long term. You might pick up the phone and call Tom Gayner, Markel’s co-CEO, knowing that his company has made numerous acquisitions in recent years. Or you might call Joe Brandon who recently took over as CEO of Alleghany, knowing that his predecessor, Weston Hicks, had a long history of such acquisitions as well.

Gaining a reputation as a buyer of businesses in the Berkshire mold is a competitive advantage for a “mini-Berkshire” for at least two reasons. First, the reputational advantage of being known as a long term owner is likely to attract owners who care about their business and might be interested in continuing to run it even after the acquisition closes. Second, since there are not very many acquirers willing or able to take a long-term view, it might be possible to acquire companies on more advantageous economic terms.

Why Would Buffett Buy a “Mini-Berkshire”?

Why would Warren Buffett rule out making small acquisitions, thereby opening up a large field for “Mini-Berkshires” to develop, and then turn around and make an offer to acquire a “Mini-Berkshire”?

The primary answer to this question is straight forward. The market capitalization of a company like Alleghany or Markel is big enough to “move the needle” at Berkshire, falls within the acquisition parameters set out in the 2017 annual report, and such a company is primarily an insurance operation — a business that Mr. Buffett knows extremely well.

To the extent that the insurance operations are healthy and produce underwriting profits, Berkshire Hathaway can easily incorporate these businesses without any changes. Ajit Jain, Berkshire Hathaway’s Vice Chairman in change of insurance operations, would simply have an additional reporting unit to oversee, but existing management of the new subsidiary would remain in place.

While insurance underwriting would remain under existing management, it is likely that the investment portfolio would be put under Mr. Buffett’s direct control. He would have the opportunity to shift allocation of the funds away from fixed income securities into common stocks, or otherwise find ways to optimize the investment returns in ways that would not be possible from a regulatory perspective for an ordinary insurer lacking Berkshire’s fortress balance sheet.

Although the non-insurance subsidiaries that Berkshire acquires would be companies that, individually, are not large enough to “move the needle”, Mr. Buffett would most likely allow the existing managers of these collections of businesses remain in charge and perhaps even give them the latitude to continue making small acquisitions as well. If there are acquired non-insurance subsidiaries that fit into some area of Berkshire that makes logical sense, then perhaps they might be moved in terms of reporting oversight, but that is likely to be a rare exception.

What process might Mr. Buffett use to evaluate a company like Alleghany or Markel? His approach is known to be simple, but not simplistic. Rather than running detailed models in Microsoft Excel, Mr. Buffett leverages seven decades of business experience to make his judgments. Assessing the economics through the numbers is indeed critical, but so is the assessment of business quality and the integrity and capacity of management.

Here are the high level questions that I think Mr. Buffett would need to answer when deciding whether he has an interest in acquiring a “mini-Berkshire”:

- Insurance Underwriting. Are the insurance operations well run? Does management have a long-term record of underwriting profits? Is there evidence to suggest that loss reserves are more likely to be redundant than insufficient? Has management shown a willingness to shrink written premiums during “soft” markets when premium pricing is inadequate to write profitably?

- Investments. How much float exists in the insurance operations? Is the float relatively stable or volatile over time (are the insurance lines short-tail or long-tail)? What is the current allocation of investments between cash, fixed income, and stocks? Is there a potential to shift funds away from fixed income to equities if the company is part of Berkshire rather than stand-alone?

- Non-Insurance Operating Subsidiaries. As a group, have the subsidiaries demonstrated consistent earnings power and attractive returns on capital employed? Does each subsidiary have honest and capable management in place who are likely to remain with their companies for a long period of time? Are the businesses relatively simple with limited exposure to technological obsolescence? Has the executive in charge of building the group of subsidiaries demonstrated good judgment with respect to the prices paid for acquisitions, and will this executive remain if Berkshire acquires the company?

How would Mr. Buffett come up with an offering price for a “Mini-Berkshire”? I suspect that he would look at the non-insurance operating subsidiaries as a group and assign a value to the group. He would then examine the investment portfolio that he would obtain from the insurance operations and consider how he would deploy the funds, which could be very different from the current allocation. In addition, he would assess whether the insurance underwriting operations are likely to operate at an underwriting profit over time, and if so, what normalized underwriting profits might look like.

Since we already know the value of the offer Berkshire has made for Alleghany, we can begin by looking at the economics of that transaction and then attempt to infer how a similar evaluation might be done for Markel.

Breaking Down the Alleghany Offer

We already know the price tag Warren Buffett has assigned to Alleghany. The all-cash transaction is valued at $11.6 billion, or $848.02 per share. I will not repeat all of the specific details that I covered in What Does Buffett See in Alleghany, posted on March 21, but I will highlight some of the key metrics.

Let’s take a 30,000 foot look at Alleghany’s non-insurance operating subsidiaries as a first step. These subsidiaries are discussed at a high level in the Alleghany Capital 2022 Overview and in the company’s March 2022 Investor Presentation.

First, let’s examine the latest financial results of the Alleghany Capital subsidiaries, as presented in the company’s fourth quarter financial supplement:

The subsidiaries are divided into industrial and consumer services groups which together generated $3.7 billion of revenue in 2021. Earnings before income tax was $291.7 million. Net income was $242.4 million (not displayed).

Management provides an adjusted pre-tax earnings figure that deducts realized capital gains and adds back amortization of intangible assets. Amortization charges occur when intangible assets are recognized upon acquisition of a business. These intangibles are written off over a period of years and represent non-cash charges. Assuming that the intangible assets associated with the acquired companies have not eroded, the charges can be disregarded, which is how Alleghany’s management has chosen to present the adjusted pre-tax earnings figure. However, for the sake of conservatism, I’m choosing to focus on actual pre-tax and net income.

Alleghany Capital’s balance sheet as of December 31, 2021 is presented below:

As of December 31, 2021, the Alleghany Capital subsidiaries had shareholders’ equity of $1,337.9 million while carrying debt of $813.7 million. The corresponding figures for December 31, 2020 (not displayed) were $1,109.1 million in shareholders equity and $590.2 million of debt.

As someone who has followed Alleghany for decades, Mr. Buffett would have not looked at these annual numbers in isolation but would also make qualitative assessments of the key subsidiaries as well as the trajectory of earnings relative to capital employed over multiple years. Clearly, he was sufficiently satisfied with the qualitative and quantitative aspects of this collection of businesses to make an offer.

How much would Mr. Buffett be willing to pay for the Alleghany Capital subsidiaries as a group? Pre-tax income for 2021 was $291.7 million and net income was $242.4 million while book value as of December 31, 2021 was $1,337.9 million. Assuming that normalized earnings power is anywhere near results posted in 2021, it would appear that Alleghany Capital is worth considerably more than its book value. Let’s make a ballpark estimate of $3.7 billion as the intrinsic value of this collection of non-insurance subsidiaries. This would be 15.3x trailing net income and 12.7x trailing pre-tax income.

So, we have a $3.7 billion ballpark estimate for Alleghany Capital. What does that imply for the value assigned to the insurance business? The total offer for the company is $11.6 billion, so let us subtract $3.7 billion to come up with a ballpark estimate of $7.9 billion for Alleghany’s insurance operations.

What does an acquirer get for that $7.9 billion?

Let’s take a look at a multi-year record of Alleghany’s insurance operations:

In 2021, Alleghany had $7.1 billion of net earned premiums and posted $195.3 million of underwriting profits. However, the company posted underwriting losses in 2017, 2018, and 2020. Prior to 2017, Alleghany posted a consistent record of underwriting profits. Over the past decade, underwriting profits have totaled over $1.6 billion. It would not be unreasonable to suppose that “normalized” underwriting profits could be around $160 million, as that would imply a combined ratio of 97.7% based on 2021 earned premiums, hardly an aggressive assumption.

As of December 31, 2021, Alleghany had a total of $12.9 billion of policyholder float, as estimated in CEO Joe Brandon’s 2021 letter to shareholders. The company had a $21.9 billion investment portfolio as of December 31, 2021 comprised of the $12.9 billion of float along with shareholders’ equity and here is how it was invested:

To summarize, for the $7.9 billion I am assigning to the value of Alleghany’s insurance operations, Berkshire is getting the following:

- An insurance underwriting operation that has generated cumulative underwriting profits of over $1.6 billion over the past ten years which plausibly implies normalized annual underwriting profits of ~$160 million.

- A $21.9 billion investment portfolio comprised of policyholder float and shareholders’ equity.

Alleghany Corporation, as a stand-alone entity, has a large fixed income allocation because of regulatory requirements. As part of Berkshire Hathaway, the fixed income allocation could be redeployed to common stocks. From Warren Buffett’s perspective, gaining control of a $21.9 billion investment portfolio and having the opportunity to shift over $16 billion from fixed income to equities would be an attractive proposition.

What is Berkshire paying for Alleghany’s insurance operations as a multiple of the book value associated with the insurance operations? Total shareholders’ equity of Alleghany at December 31, 2021 was $9,186.9 million. The book value of Alleghany Capital is $1,337.9 million, implying book value for the insurance operations of approximately $7,849 million. If Berkshire is paying $7.9 billion for the insurance operations, this would roughly approximate book value.

To summarize, Berkshire Hathaway is paying $11.6 billion in exchange for:

- Non-insurance subsidiaries that generated $242 million in net income in 2021 to which I attribute ~$3.7 billion of value.

- Insurance subsidiaries that posted underwriting profits of $195.3 million in 2021, with an investment portfolio of $21.9 billion as of December 31, 2021 comprised of $12.9 billion of policyholder float with the balance representing shareholders’ equity. I attribute $7.9 billion to the insurance subsidiaries which approximates the book value attributable to the insurance group.

Now, let’s take a look at what these conclusions imply for Berkshire’s potential interest in Markel Corporation.

Looking at Markel from Berkshire’s Perspective

I have closely followed Markel Corporation for over a decade and owned shares of the company from March 2011 until selling the last shares of my position in March 2022 when the stock advanced significantly in a short period of time. I have written about Markel several times on The Rational Walk website, with many of the articles including discussion of the company’s Markel Ventures collection of non-insurance operating subsidiaries.

Two articles might be of particular interest for readers looking for background information on Markel Ventures:

A Closer Look at Markel Ventures published on May 20, 2016

Markel Ventures Gains Momentum published on November 3, 2016

Although these articles are more than five years old, the underlying principles behind Markel’s move into non-insurance subsidiaries starting in 2005 remain highly relevant today. Since 2016, Markel has continued to add non-insurance operating subsidiaries under the Markel Ventures umbrella and the importance of this group to the overall enterprise has grown. Links to each of the subsidiaries in the group can be found on the Markel Ventures website.

For purposes of this article, I will attempt to follow the general process used in the preceding section on Alleghany. First, I will attempt to estimate what value Berkshire Hathaway might assign to the Markel Ventures group of companies. Then, I will look at the insurance operations. Rather than using a known acquisition price, I will use Markel’s market capitalization as of April 14, 2022. On that day, Markel stock closed at $1,475 per share which implies a market capitalization of ~$20.1 billion.

The exhibit below shows the past five years of income statements for Markel Ventures:

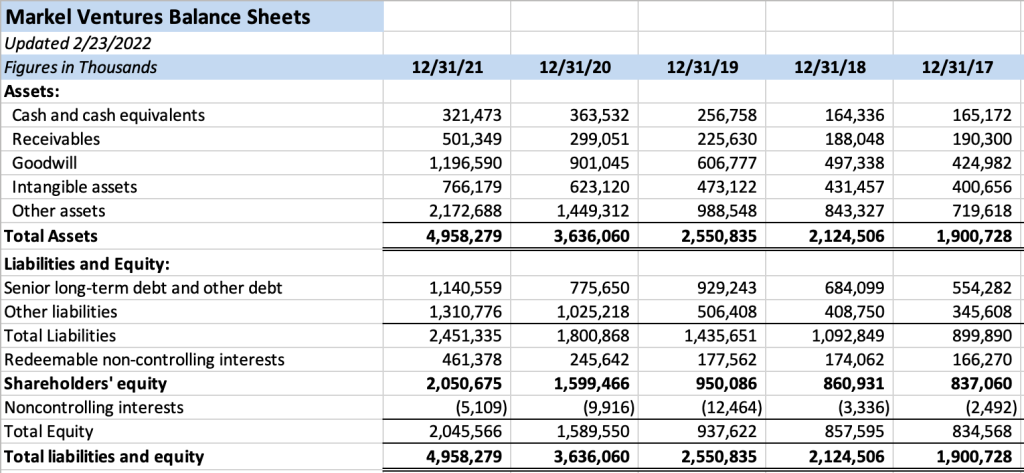

The following exhibit shows the past five years of balance sheets for Markel Ventures:

From a standing start in 2005, Markel’s co-CEO Tom Gayner has committed significant capital to growing the Markel Ventures group. In his 2021 letter to shareholders, Mr. Gayner comments extensively on Markel Ventures from which I select a short excerpt below:

“In 2021, Markel Ventures produced $3.6 billion in revenues and $403 million in EBITDA. Cumulatively we’ve invested approximately $3.4 billion to acquire and fund these businesses. Cumulatively these businesses have built up cash balances and returned $1.5 billion to Markel. In economic terms, we’ve got a net investment of $1.9 billion on the line and in 2021 alone they produced EBITDA of $403 million. The reality is even better than those numbers would suggest since we laid out the cash for Buckner and Metromont near year end and show the full amount of capital committed and only partial-year EBITDA against that outlay.”

The overall track record is indeed impressive, but I will avoid making qualitative comments on the specific businesses for the sake of keeping this already long article to a semi-reasonable length. For purposes of this article, I am mainly interested in how Warren Buffett would view this collection of businesses in the aggregate.

For Alleghany Capital, I guessed that Mr. Buffett might value the collection of businesses at $3.7 billion, which represents 15.2x trailing net income. There could be important qualitative differences between Markel Ventures and Alleghany Capital that could justify a higher (or lower) multiple. But for consistency, I will use a similar multiple to arrive at a valuation of Markel Ventures of ~$2.7 billion, as a round number. This is ~15.5x trailing net income.

I’m sure that Markel’s management considers the true economic value of Markel Ventures to be far higher than $2.7 billion. For one thing, the $57.6 million charge for amortization of intangible assets in 2021 is not likely to represent a real economic expense. Are there economic characteristics of Markel Ventures businesses that are more attractive than Allegheny Capital’s businesses and deserving of a higher multiple? This is definitely possible. In any case, if one disagrees with this figure, it’s easy enough to change the following discussion to reflect a higher (or lower) value.

If we accept $2.7 billion as a plausible valuation for Markel Ventures and subtract this figure from the company’s $20.1 billion market cap, we arrive at a $17.4 billion implied price for the insurance subsidiaries. Let’s take a look at recent history of insurance underwriting as well as the investment portfolio.

The following exhibit shows a high level summary of Markel’s underwriting results for the past ten years:

I’ve maintained the following chart for an even longer term view of Markel’s excellent underwriting record:

In 2021, Markel posted underwriting profits of $628.1 million on earned premiums of $6.5 billion, for a combined ratio of 90.3%. Cumulative underwriting profits over the past decade exceed $2 billion. If we take an average of ~$200 million of underwriting profits per year and consider this “normalized”, that would imply a normalized combined ratio of ~96.9% against 2021 earned premium volume. It seems very plausible and conservative to suppose that Markel could post average underwriting profits in the range of $200 million annually over time.

Next, let’s take a look at Markel’s investment portfolio. The following exhibit shows Markel’s investment portfolio over the past decade:

Markel had an investment portfolio of $23.4 billion as of December 31, 2021 which isn’t that much larger than Alleghany’s $21.9 billion portfolio. However, the composition of Markel’s portfolio is very different. While Alleghany has 73.3% of its portfolio in fixed income securities and 16.8% in equity securities, Markel has 53.8% in fixed income and 38.5% in equity securities.

Tom Gayner has been managing Markel’s equity portfolio for over three decades and has an excellent long-run track record, as shown by the exhibit below:

The aggregate results over many decades demonstrates that Mr. Gayner has uncommon skill and Markel has benefited considerably from his talents in stock selection. Nevertheless, as Mr. Gayner explained in his annual letter, Markel must still maintain a significant fixed income portfolio to satisfy insurance regulators.

Following the approach I used to evaluate Alleghany’s insurance valuation, let’s repeat the exercise for Markel. For an implied price of $17.4 billion, an acquirer would get the following:

- An insurance underwriting operation that has generated cumulative underwriting profits of over $2 billion over the past ten years which plausibly implies normalized annual underwriting profits of ~$200 million.

- A $23.4 billion investment portfolio comprised of policyholder float and shareholders’ equity.

If we take Markel’s total shareholders’ equity as of December 31, 2021 of $14.1 billion and subtract the ~$2.1 billion of equity attributable to Markel Ventures, we arrive at an implied book value of ~$12 billion for Markel’s insurance businesses. Therefore, our implied price of the insurance subsidiaries of $17.4 billion is ~1.45x book value. In contrast, the implied price of Alleghany’s insurance subsidiaries is approximately equal to its book value.

What can we conclude from this exercise?

Although one can certainly differ on the assumptions used to value the non-insurance subsidiaries of Alleghany and Markel, and there could be important qualitative differences justifying changes, it is clear that the implied value of the insurance subsidiaries is considerably higher for Markel than what Mr. Buffett is paying for Alleghany’s insurance subsidiaries.

The question is whether the higher implied price of Markel’s insurance business can be justified. Markel is likely to have somewhat higher normalized underwriting profits than Alleghany over time. However, there is less upside in terms of potentially reallocating Markel’s fixed income portfolio to equities.

It seems to me that one major factor at Markel is the presence of Tom Gayner and the skills that he brings to the management of the investment portfolio. In addition, his charismatic leadership style clearly inspires loyalty from employees and is likely to attract family-run companies that might be willing to sell to Markel Ventures.

It is exceedingly hard to imagine an acquisition of Markel making sense for Berkshire Hathaway at anywhere near the current price without securing the services of Tom Gayner for a lengthy period of time. If he joins Berkshire as its third portfolio manager, in addition to Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, and also continues building up Markel Ventures, paying a premium price for Markel could be justified. In the absence of Mr. Gayner, I am not sure that a deal would make sense.

Of course, there are two sides to every deal. In the case of Markel, there are Markel family interests who would face significant capital gains taxes if the company was sold for cash. Mr. Buffett was not inclined to offer Berkshire stock for Alleghany and would probably be reluctant to do so for Markel. Mr. Gayner has been at Markel for decades and has been “painting his own canvas”, and seems inclined to continue doing just that in the years and perhaps even decades to come.

Would Mr. Gayner be willing to work for Berkshire Hathaway? Of course, this is impossible to know. Perhaps he might be interested if he was considered a potential successor for Mr. Buffett. However, Berkshire’s board has already indicated that Greg Abel is the executive likely to be named the next CEO of Berkshire. Mr. Abel is 59 and Mr. Gayner is 60 based on recent proxy statements, making Mr. Gayner an unlikely eventual successor for Mr. Abel.

The final factor that would preclude a deal is that Mr. Buffett would not be able to acquire Markel for its current market capitalization. He would almost certainly need to offer a significant premium. This would make the acquisition even more demanding than what I have outlined above. Of course, this could change if Markel shares decline, but it is hard to see Berkshire acquiring the company for much less than its current market value even if the market quotation declines considerably.

Conclusion

Based on studying the situation, I believe that it is quite unlikely that Berkshire Hathaway will acquire Markel Corporation anytime soon. This could change in the future, but any deal would need to be attractive to both companies.

In particular, the Markel family’s tax situation would need to be addressed in a satisfactory manner and Mr. Gayner would have to be amenable to working for Berkshire. Otherwise, Berkshire is likely to be better off looking for other insurance acquisitions similar to Alleghany where the valuation is considerably less demanding.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk LLC own shares of Berkshire Hathaway common stock.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this newsletter constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC.

Your privacy is taken very seriously. No email addresses or any other subscriber information is ever sold or provided to third parties. If you choose to unsubscribe at any time, you will no longer receive any further communications of any kind.

The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

- Warren Buffett has often stated that his annual letter is written months before publication. For example, refer to his interview with Charlie Rose posted on April 14, 2022. So, we cannot necessarily assume that his mindset on February 25, 2022 was reflected in the letter which was finalized long before that date. [↩]

- Although my lengthy report on Berkshire Hathaway published in February 2011 is out of date with respect to today’s company, it still could be interesting to those who wish to read about Berkshire’s early days. For a brief except from that report, see From Cigar Butts to Business Supermodels. I also recommend Capital Allocation: The Financials of a New England Textile Mill by Jacob McDonough, which I reviewed on The Rational Walk in 2020. [↩]