TransDigm Group is a leading designer and producer of engineered components that are used in nearly all commercial and military aircraft. The company was founded in 1993 by Nicholas Howley, who currently serves as Chairman and CEO, and Douglas Peacock who is a member of the Board of Directors. TransDigm has grown rapidly over the years through acquisitions and organic growth using a private equity-like business model. Although the company went public in 2006, the business model has not changed. Since 1993, management has compounded revenue at an annualized rate exceeding 20 percent. Profitability has grown even more rapidly through margin expansion.

At the outset, it is worth noting that TransDigm uses a highly leveraged capital structure and is not a statistically cheap stock. The company has negative shareholders’ equity, $8.3 billion in debt, a market capitalization of $12 billion and total enterprise value of approximately $20 billion. Earnings before interest, financing costs, and income tax was $1.1 billion in fiscal 2015 so the EV/EBIT ratio is quite high at approximately 18x. However, TransDigm has many interesting characteristics including management’s history of effective capital allocation and the company’s large and growing economic moat. The company was mentioned in The Outsiders as a contemporary analog for the track record of Capital Cities. Even if TransDigm shares are not cheap, the business is interesting enough to warrant further study. It is never a waste of time to examine the track record of a highly successful management team.

Overview

TransDigm specializes in the design, production, and distribution of highly engineered aviation parts and components. Since its founding in 1993, the company has acquired 56 businesses including 41 since the IPO in 2006. Six operating units were acquired for a total of $1.6 billion in fiscal 2015 which was the company’s biggest year for acquisition activity up to this point. Management focuses on capital allocation and allows subsidiaries to operate with a significant amount of autonomy through a decentralized organizational structure.

The key to TransDigm’s economic moat is related to the nature of the aerospace industry. A typical commercial or military aircraft platform takes many years to develop and can be produced for 20 to 30 years. The lifespan of an aircraft can be 25 to 30 years so the required component parts can have a product life cycle in excess of 50 years. Once an aircraft part is incorporated into the design of a new platform, sales are generated to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) such as Boeing and Airbus. Aftermarket sales continue for the life of the aircraft. There is an extensive selection and qualification process for critical parts that often requires FAA certification.

Over 90 percent of the company’s revenues are generated from proprietary products and approximately 75 percent are from products where the company is the only source of supply. Approximately 54 percent of revenues are from aftermarket sales where the gross margin is significantly higher than from OEM sales. While the sale of new aircraft tends to be cyclical in nature, aftermarket sales are much more steady and highly correlated with total worldwide revenue passenger miles flown. Revenue passenger miles has tended to grow at an annual rate of 5 to 6 percent. Since 1970, revenue passenger miles have doubled every 15 years. The exhibit below, taken from the company’s February 2016 investor relations presentation (pdf), illustrates the growth of the installed base of commercial aircraft over time as well as the importance of the aftermarket channel.

The presentation also includes a slide that is quite revealing in terms of TransDigm’s growth prospects as well as the nature of aftermarket parts as a percentage of airline operating expenses:

Maintenance only accounts for 9 percent of airline operating expenses but obviously the quality of the components used in maintenance activities is extremely important. Other than the fact that TransDigm is the single source provider for most of its product lines, airlines have little incentive to “shop around” for a lower bidder given the low cost of replacement parts relative to overall operating expenses. This provides a great deal of pricing power to TransDigm as well as other aftermarket parts manufacturers. Obviously not all parts are equally critical (a lavatory component is less critical than a fuel pump), but in general, price sensitivity is lower for critical parts especially when the cost of the part is a small component of overall operating expenses.

Operating Results

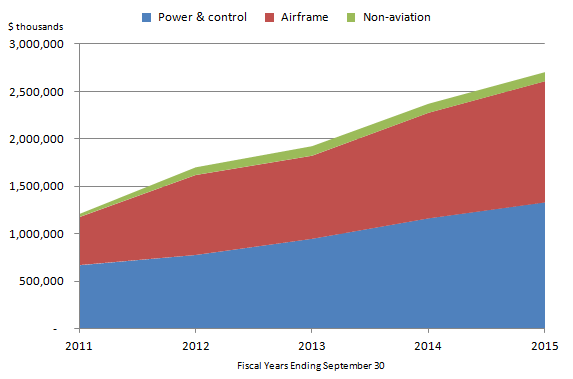

TransDigm’s overall results since inception have been extremely strong with revenue growing at an annualized rate of 20.1 percent and EBITDA growing at 24.5 percent, as shown in the exhibit below. When looking at charts like this, it is important to examine whether rapid growth from early years has slowed down more recently but this does not appear to be the case for TransDigm. In fact, growth rates over the past five years have been roughly in line with the long term trend.

The market has not ignored the strong performance since the 2006 IPO. Over the past decade, shares have appreciated by over 800 percent. In addition to share price appreciation, the company has paid a total of $67.50 per share in special dividends.

TransDigm is organized into three reporting segments:

- The Power & Control segment includes businesses that develop, produce, and distribute components that predominantly provide power or control to the aircraft using a variety of motion control technologies. Products include items such as pumps, valves, ignition systems, and specialty electric motors and generators. This segment accounted for 49 percent of revenue and 52 percent of EBITDA (as defined by management) in fiscal 2015 (year ended on September 30, 2015).

- The Airframe segment includes businesses that develop, produce, and distribute components that are used in non-power airframe applications. Products include items like latching and locking devices, cockpit security components, audio systems, lavatory components, seat belts and safety restraints, and lighting systems. Airframe accounted for 47 percent of revenue and 46 percent of EBITDA in fiscal 2015.

- The Non-aviation segment targets markets outside the aerospace industry such as seat belts and safety devices for ground transportation, child restraint systems, satellite and space systems, and parts for heavy equipment used in mining and construction. Non-aviation accounted for 4 percent of revenue and 2 percent of EBITDA in fiscal 2015.

The exhibit below shows TransDigm revenue by segment over the past five fiscal years. The percentage of revenue provided by each segment has not varied dramatically over this time frame despite a significant number of new acquisitions so the mix of business provided by acquisitions has tended to be aligned with the existing mix.

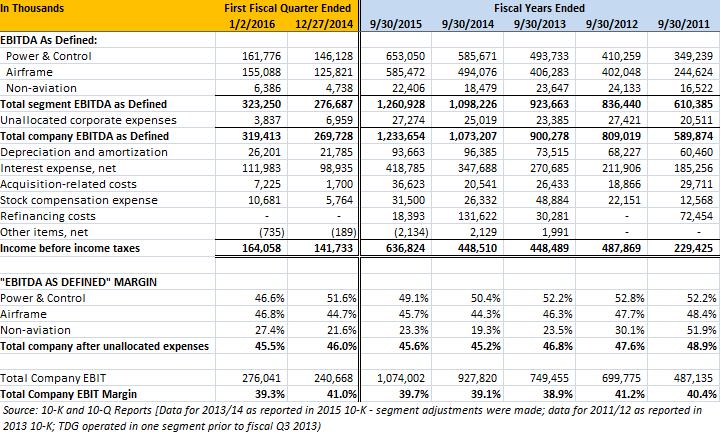

The exhibit below shows segment and total company results over the past five years as well as the first quarter of fiscal 2016. Management has developed a metric known as “EBITDA as defined” which is used internally to manage the business and evaluate results. Some of the adjustments, such as the exclusion of stock compensation expense and acquisition related costs, seem suspect for analytical purposes but are probably not meaningful enough to change broad conclusions regarding operating performance:

We can see that Power & Control tends to offer the highest margins, followed closely by Airframe. Non-aviation, which is a very small part of the company, has significantly lower margins. A high level look at these figures demonstrates that the company is obviously very profitable and that the business appears to benefit from entrenched economic moats. Notably, margins have held up well over the period despite several acquisitions. This indicates that management has been able to successfully find acquisitions that share economic characteristics similar to the existing lineup of business units or has been able to bring up margins after acquisitions.

Approximately two-thirds of revenue in fiscal 2015 came from domestic customers with the rest from direct sales to foreign customers. Over the past decade, the geographic mix of business has shifted slightly toward foreign customers. In fiscal 2015, approximately 9 percent of revenue came from businesses acquired over the past fiscal year. Net income was $444 million in fiscal 2015. The company’s tax rate has tended to be in the low-mid 30 percent range.

TransDigm’s free cash flow typically exceeds net income. The business is not capital intensive and there are regular non-cash amortization charges that depress net income relative to operating cash flow. Additionally, the company believes in using significant equity based compensation. From fiscal 2004 to 2015 (which encompasses all publicly available data filed with the SEC), the company generated aggregate net income of $2.2 billion and free cash flow of $2.9 billion.

Acquisition History and Capital Structure

TransDigm has been very acquisitive over the years. Incorporating smaller parts manufacturers into the TransDigm system has been a major factor driving the kind of revenue growth discussed above. The exhibit below shows all of the acquisitions the company has made over the years:

The following exhibit aggregates selected data from TransDigm’s publicly available cash flow statements since 2004 and provides a good summary of how management has funded its activities at a very high level:

We can see that the company has used more than its aggregate free cash flow to return capital to shareholders. Leverage has effectively funded all of the company’s acquisition activity as well as additional return of capital to shareholders. Leverage is a key component in management’s overall strategy of providing “private equity-like growth” in the value of the stock. Management targets 15 to 20 percent annualized growth and key performance based compensation is only fully granted if annualized growth reaches 17.5 percent. The exhibit below shows that TransDigm has historically varied its leverage based on the availability of acquisition candidates as well as the timing of cash return to shareholders:

A leveraged capital structure is a key component of management’s strategy of delivering 15 to 20 percent annualized growth:

As of January 2, 2016, the end of the company’s first quarter of fiscal 2016, total debt was $8.3 billion. Total stockholders’ equity was a negative $964 million and tangible equity was negative $7.1 billion due to the presence of significant goodwill and intangible assets on the balance sheet attributable to past acquisitions.

Despite the fact that the company has negative tangible equity, it is quite clear that economic goodwill is very high. The evidence of significant economic goodwill is the fact that the company regularly posts high operating margins and generates significant free cash flow. Tangible equity is not required to operate this business. Whether one considers the highly leveraged capital structure to be appropriate or not is partly dependent on risk tolerance. Although the business seems to have all of the characteristics of a steady and growing annuity, and qualitative factors discussed earlier support this viewpoint, negative surprises leave no margin of safety from a balance sheet perspective. TransDigm has a shareholder constituency that appears to embrace the leveraged capital structure in exchange for higher anticipated returns on their investment.

Boeing’s Push Into Airplane Parts

Earlier this week, The Wall Street Journal reported that Boeing is planning a new push into the airplane parts business. Apparently Boeing’s management has not been oblivious to the high margins enjoyed by parts manufacturers and distributors. Boeing has the power to grant licenses to suppliers to sell proprietary parts to airline customers. The company’s effort to gain control over the distribution of aftermarket parts has been ongoing for several years.

There is a risk that manufacturers could be forced to distribute aftermarket parts through Boeing which would take a cut of the revenue. Assuming that pricing to the end customer stays constant, this would imply margin pressure for parts manufacturers in the aftermarket channel. Boeing, and other airplane manufacturers, already exert pricing pressure for OEM parts which is why the OEM channel is lower margin than the aftermarket channel. Parts manufacturers count on higher aftermarket margins to offset the initial cost of design and development. If the margins for OEM and aftermarket channels eventually converge, it would imply much lower profitability for the parts manufacturers as a group.

The Wall Street Journal included a chart showing the exposure of a number of companies producing aftermarket parts:

It is not clear at this point whether the concerns raised in the Wall Street Journal article will have much of an impact on TransDigm. The excellent margin characteristics of the aftermarket business have not been a secret in the past and Boeing has wanted a piece of the action for many years. The characteristics of the economic moat described earlier indicate substantial protection for TransDigm’s profitability. However, over the long run, the risk of Boeing or other airplane manufacturers encroaching on this territory should be kept in mind.

Conclusion

TransDigm has a highly entrenched position in most of its markets and has enjoyed very strong operating results in recent years. Management has grown the business organically as well as through the aggressive pursuit of acquisitions. These acquisitions have been funded predominantly with debt and TransDigm has a very leveraged capital structure. The valuation of the company does not appear to be cheap by conventional measures, although if management is able to continue compounding free cash flow at historical rates, continuing shareholders are likely to be rewarded.

Investors take many different approaches when deciding which companies warrant further study. Everyone has limited time available for research and it is tempting to focus on companies that are statistically cheap and could be candidates for investment immediately. However, sometimes limiting the research process to candidates that could be immediately actionable results in not spending time looking at excellent companies that could be candidates at some point in the future. Assuming that an investor is comfortable with the leveraged business model, it is possible that shares could be attractive during a future market decline. However, stepping back a bit from the investment process, we should bear in mind that studying great managers with impressive business track records is rarely a waste of time even if it doesn’t lead directly to investment candidates.

Disclosure: No position in TransDigm Group