“I have great hopes in this direction for machines that will rival or even surpass the human brain. This area, known as artificial intelligence, has been developing for some thirty or forty years. It is now taking on commercial importance. For example, within a mile of MIT, there are seven different corporations devoted to research in this area, some working on parallel processing. It is difficult to predict the future, but it is my feeling that by 2001 AD we will have machines which can walk as well, see as well, and think as well as we do.”

— Claude Shannon, Kyoto Prize Speech, November 11, 1985

Claude Shannon is most famous for his groundbreaking work related to information theory and communications but he was also a multi-disciplinary thinker and a lifelong tinkerer. He was never satisfied with applying his genius to the abstract problems of pure mathematics, instead always striving to use mathematical concepts to solve concrete problems in multiple disciplines.

There is no Nobel Prize dedicated to mathematics, but Shannon received many other honors during his career including the Kyoto Prize in 1985. In his acceptance speech, he predicted that machines would soon surpass human capabilities. While he might have been too optimistic by a couple of decades, Shannon clearly could see the rise of machine learning and artificial intelligence on the not-too-distant horizon.

Thirty-five years before accepting the Kyoto Prize, Shannon developed one of the earliest examples of machine learning when he built Theseus, a mechanical mouse that could figure out its way out of a maze. Theseus had the ability to remember the architecture of a maze and figure out how to get to a piece of “cheese” at the end. Shannon proved that the mouse could learn by rearranging the contours of the maze and showing that Theseus could learn the new arrangement by trial and error.

Shannon demonstrated how Theseus works in this 1952 Bell Labs video:

While Shannon’s presentation is a bit stilted and not terribly impressive by twenty-first century standards, consider that this “intelligent” mechanical mouse was created over seven decades ago! It was based on telephone switching technology that Shannon worked with during his years at Bell Laboratories. Shannon created the Theseus mouse at his extensive home laboratory where he engaged in countless experiments just for the fun of gaining knowledge. He freely admitted that much of his time was spent on “totally useless things” of no apparent commercial value.

The reality is that the intense intellectual curiosity of a man like Claude Shannon is never directed in a “useless” manner because many discoveries are only recognized as important when looking back at history. Shannon’s playful attitude toward scientific inquiry combined with a good dose of eccentricity makes him a fascinating subject for a biography. In A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age, Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman present the portrait of a genius who saw no distinction between work and play. As Ed Thorp says on the back cover, Claude Shannon comes alive in the pages of this book.

My book spreadsheet indicates that I first read A Mind at Play in September 2017, a few months after I read Ed Thorp’s autobiography, A Man for All Markets. There is no doubt that I selected Shannon’s biography because I read about his association with Ed Thorp in A Man for All Markets.

I wrote an article about of A Man for All Markets but for some reason I did not write about A Mind at Play. When I recently realized this oversight, I decided to re-read A Mind at Play and put together some thoughts. With all the excitement over artificial intelligence, going back to Shannon’s life seems timely and appropriate.

Information Theory

The vast amount of information we encounter in our everyday lives is something that people under thirty-five simply take for granted because they cannot recall a world without the internet. For those of us who are a decade or two older, the rise of the internet looms large in our memories as a demarcation point. In my case, the internet went mainstream shortly after I graduated from college in 1995.

By the late 1990s, students and researchers went from microfiche to the worldwide web. By the mid-2000s, the internet was thoroughly mainstream although somewhere short of universal. The introduction of the iPhone in 2007 and the subsequent rise of the smartphone industry represented the democratization of the internet. By the early 2020s, 85% of Americans carried a supercomputer in their pockets.

As Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman write at the end of the book, “there is something ungrateful and grasping in enjoying our bounty of information without bothering to understand how it got here.”

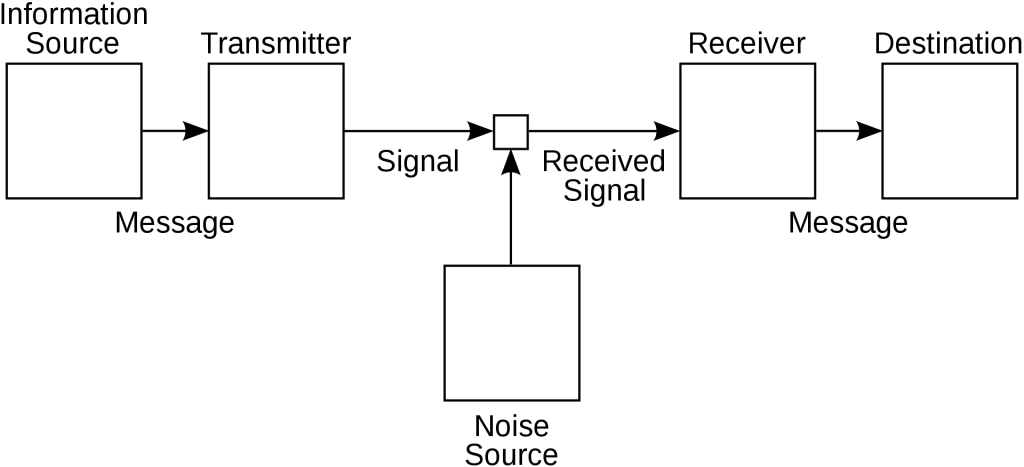

It is impossible to understand how we got here without studying the life of Claude Shannon who is widely considered to be the “Father of Information Theory”, although his seminal work can be more accurately characterized as how information is transmitted from its source to its intended destination through channels that inevitably introduce an element of noise, as seen in the diagram below:

Prior to Shannon’s 1948 paper, A Mathematical Theory of Communication, the uncertainty caused by noise in a transmission channel was only abstractly understood. In the 1850s, the first attempts to install transatlantic telegraph cables initially met with failure due to rapid degradation of the cable which introduced more and more noise until the signal could not get through. A more durable cable eventually made transatlantic communications possible starting in the mid 1860s. Solving problems of the telegraph and telephone systems became a critical task for scientists.

Claude Shannon began working on switching circuits in 1936 at MIT under the direction of Vannevar Bush, one of the most important scientists of the twentieth century. Shannon’s master’s thesis was on the use of switching circuits in telephone call routing networks, background that would prove useful when he joined Bell Labs. Devoted to basic scientific research, Bell Labs proved to be an ideal place for Shannon to pursue his interests, apparently never directly telling Shannon what to work on.

Shannon’s intellectual interests coincided perfectly with the practical problems facing the Bell System which maintained the legacy telegraph system as well as the telephone network during the 1940s. Information had to be sent through this extremely complex network as efficiently as possible while dealing with noise.

Shannon developed what is known as the noisy-channel coding theorem, sometimes referred to as “Shannon’s Limit”, that defined the maximum rate of error-free transmission through a channel for a given level of noise. The key to overcoming noise in transmission is the degree of redundancy of the message which acts as a “shield” against the damage that can be caused by noise.

In chapters fifteen and sixteen, Soni and Goodman provide an account of information theory and Shannon’s contributions to the field in just forty pages. The discussion is suitable for a general audience but is still relatively complicated. After reading these chapters more than once, I do not think that the subject can be condensed or summarized any further and I would encourage readers interested in exploring information theory in more detail to read the book.1

Shannon and Thorp

Claude Shannon’s fame increased dramatically in the early to mid-1950s. In 1956, MIT recruited Shannon with a full professorship. However, he was considered so important to Bell Labs that they kept him on the payroll with no defined responsibilities!

At the age of 40, Shannon was in a position akin to an emeritus professor with a light teaching load and the ability to pursue projects that piqued his intellectual interests. Shannon and his wife purchased a home near MIT that they named “entropy house” where he constructed labs devoted to experimentation and tinkering.

Entropy house was the setting for a fascinating collaboration between Ed Thorp and Claude Shannon in the early 1960s. As I discussed in my review of Ed Thorp’s book, the collaboration involved creating a wearable electronic device to help win the game of roulette. Ed Thorp’s account of the development of this computer and his collaboration with Claude Shannon is very interesting reading.

“Shannon lived in a huge old three story wooden house once owned by Jane Addams on one of the Mystic Lakes, several miles from Cambridge. His basement was a gadgeteer’s paradise. It had perhaps a hundred thousand dollars (about six hundred thousand 1998 dollars) worth of electronic, electrical and mechanical items. There were hundreds of mechanical and electrical categories, such as motors, transistors, switches, pulleys, gears, condensers, transformers, and on and on. As a boy science was my playground and I spent much of my time building and experimenting in electronics, physics and chemistry, and now I had met the ultimate gadgeteer.

Our work continued there. We ordered a regulation roulette wheel from Reno for $1,500 and assembled other equipment including a strobe light and a large clock with a second hand that made one revolution per second. The dial was divided into hundredths of a second and finer time divisions could be estimated closely. We set up shop in ‘the billiard room,’ where a massive old dusty slate billiard table made a perfect solid platform for the roulette wheel.”

In the summer of 1961, Shannon and Thorp went to Las Vegas with their wives to test out the device. This was at a time when the Nevada gambling industry had mafia ties and testing this type of system was far from risk free! They were nearly caught.

“Claude generally stood by the wheel and timed, and for camouflage recorded numbers like just another ‘system’ player. I placed bets at the far end of the layout where I paid little attention to the ball and rotor. We acted unacquainted. The wives monitored the operation, checking to see whether the casino suspected anything and if we were inconspicuous. Once a lady next to me looked over in horror. I left the table quickly and discovered the speaker peering from my ear canal like an alien insect.”

Ultimately, the device proved to be successful:

“The wires to the speaker broke often, leading to tedious repairs and the need to rewire ourselves. This stopped us from serious betting on this trip. Except for the wire problem, the computer was a success. We could solve this with larger wires and by growing hair to cover our ears, a conspicuous style at the time, or persuade our reluctant wives to ‘wire up.’”

The Shannon-Thorp collaboration ran its course when Thorp left MIT. Thorp’s interests eventually shifted from gambling to investing in financial markets, as he describes in A Man for All Markets. It’s interesting to see this story told by Ed Thorp in his autobiography and the same story discussed in Shannon’s biography. While Thorp may have been financially motivated, it is likely that Shannon participated in this project based mostly on intellectual curiosity.

Playing the Stock Market

By the late 1960s and 1970s, Claude Shannon was more than financially secure due to the combination of his salaries at MIT and Bell Labs coupled with early investments in several technology companies. Shannon was also a friend of Henry Singleton who he had known since college. Singleton put Shannon on the board of Teledyne. Shannon’s investment in Teledyne compounded at 27 percent over a quarter century.

Despite having no need for additional income, Claude Shannon and his wife followed the stock market “obsessively” and, according to their daughter, stocks became a frequent topic of conversation at home. Why did Shannon play the stock market?

“In a way, Shannon’s interest in money resembled his other passions. He was not out to accrue wealth for wealth’s sake, nor did he have any burning desire to own the finer things in life. But money created markets and math puzzles, problems that could be analyzed and interpreted and played out. Shannon cared less about what money could buy than about the interesting games that money made possible.”

It is also likely that Betty Shannon, Claude’s wife, was the driving force behind the couple’s obsession with markets. Betty Shannon was also a mathematician and shared many of Claude’s interests. She ran the family’s financial affairs and the couple considered themselves “gamblers”. Shannon eventually formulated stock picking theories and even presented them at MIT to a standing room only crowd. However, he never put his mathematical theories into practice due to high commission costs. His work on the subject was never published.

Ultimately, the Shannons decided that technical analysis mattered much less than the fundamentals.

“My general feeling is that it is easier to choose companies which are going to succeed than to predict short term variations, things which last only weeks or months, which they worry about on Wall Street Week.”

Soni and Goodman report that the bulk of the Shannons wealth was concentrated in Teledyne, Motorola, and HP stock after getting in on the ground floor, and “the smartest thing Shannon did was hold on.” For all of Claude Shannon’s mathematical brilliance, he apparently concluded that buy and hold investing made the most sense.

Artificial Intelligence

Claude Shannon developed Theseus, the mechanical mouse, when he was in his mid-thirties, but artificial intelligence was a topic that captivated his interest for the rest of his life. He stated that his “fondest dream is to someday build a machine that really thinks, learns, communicates with humans and manipulates its environment in a fairly sophisticated way.”

Will it ever be possible to create a machine that truly acts like a human brain?

Shannon clearly thought so:

“I think man is a machine. No, I am not joking, I think man is a machine of a very complex sort, different from a computer, i.e., different in organization. But it could be easily reproduced — it has about ten billion nerve cells… And if you model each one of these with electronic equipment it will act like a human brain. If you take Bobby Fischer’s head and make a model of that, it would play like Fischer.”

The quote above is from an interview in 1980, seventeen years before the Deep Blue computer defeated chess world champion Garry Kasparov. Shannon’s aspirations for artificial intelligence were clearly more expansive, but his example of a computer capable of beating the most talented human in chess quickly came true.

Claude Shannon’s view of artificial intelligence was both expansive and optimistic. When viewed retrospectively, his predictions seem particularly prescient even if it has taken longer than he expected to reach various milestones.

A Sad Conclusion

Claude Shannon lived to see the dawning of the twenty-first century but unfortunately his brilliant mind started to decline by the mid-1980s. Diagnosed with the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, Shannon continued his intellectual pursuits and tinkering for as long as possible but his family noted a relatively quick mental decline. After suffering a fall in 1993, he spent the rest of his life in a nursing home.

Alzheimer’s is always a terrible diagnosis but somehow it seems even more cruel when it ravages a mind as brilliant as Claude Shannon’s. To add to the sense of injustice, had he remained mentally competent until his death in 2001, Shannon would have been aware of how the internet revolutionized the world and the fact that the field that he pioneered played such an instrumental role. He would have understood the advances in artificial intelligence that made Deep Blue possible and would have had a sense of things to come. Alzheimer’s robbed him of this knowledge.

It’s a cliché to say that we stand on the shoulders of giants, but this happens to be true. Artificial intelligence has made massive advances over the past few years and will certainly have an even more profound impact in the years to come.

I tend to take a cautious and skeptical approach when it comes to AI. The main reason I chose to read A Mind at Play for the second time is to refresh my memory regarding Shannon’s thinking on the subject. While his optimism isn’t entirely reassuring when it comes to the prospect of AI getting out of control, it is certainly notable that the father of information theory believed that AI would be a boon for humanity rather than the cause of our destruction.

Copyright, Disclosures, and Privacy Information

Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and all content is subject to the copyright and disclaimer policy of The Rational Walk LLC. The Rational Walk is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

- The math and concepts discussed in chapters 15 and 16 are relatively straight forward, although a search on the internet reveals significant added complexity that is hard to comprehend without pursuing serious technical studies. Soni and Goodman have done a good job explaining Shannon’s work to a general audience and I am sure condensing this information into forty pages took months or even years of effort. Short of creating a much longer article and being presumptuous enough to think that I could distill the topic any further, I am more comfortable recommending that readers interested in learning more about information theory should read the book. Hopefully the limited discussion here has been enough to spark the reader’s interest to refer to the book to learn more. [↩]